|

Brazil

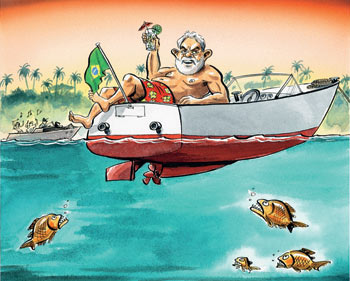

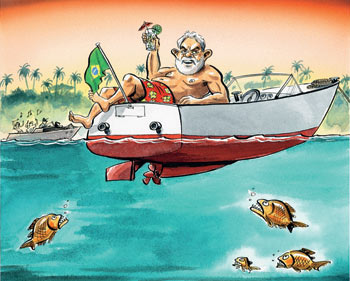

Lazy, hazy days for lucky Lula

Better times sap the will to reform, among government and opposition

alike

| |

Peter

Schrank |

|

THESE are

strange times in Brazil. Every morning, the country's main newspapers

bring fresh instalments in a slew of corruption scandals lapping

around the government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. The

latest one involves the president of the senate, Renan Calheiros, a

Lula ally. He faces widespread calls to resign over allegations that a

lobbyist for a construction firm made regular payments to a journalist

with whom he had an affair and a child. In another case, involving

illegal slot-machines, federal police questioned one of Lula's

brothers over alleged influence-peddling.

The government

seems trapped in torpidity. Six months into his second term, Lula has

just completed his cabinet, adding a 37th minister — one for

“strategic planning”. But what are all these ministers for? The

government's agenda is unambitious, and its reaction to events often

tardy and fumbling. Take the chaos that has gripped Brazil's airports

since October as a result of go-slows by disgruntled air-traffic

controllers. Marta Suplicy, the tourism minister, seemed to sum up the

official stance when, to much outrage, she suggested that travellers

should “relax and enjoy” the long delays. On June 22nd the government

finally sacked 14 controllers — an action it could have taken months

ago.

Brazilians often

gripe that their politicians, ensconced in Brasília, live in pampered

isolation from everyday realities. Yet perhaps it is the newspapers,

for all the polished competence of their investigations, which are

living in a bubble. They are read by the few: Folha de São Paulo, the

biggest-selling daily, shifts only 300,000 copies in a country of 190m

people. Meanwhile, the average Brazilian is rather content, less

interested in the television news than the soap opera that follows it.

Scandals notwithstanding, the president is hugely popular. In São

Paulo's gritty periphery “everyone loves Lula,” says Afonso Gonçalves,

who owns a small supermarket in the suburb of São Bernardo, where the

president was once a trade-union leader. “He focused on the poor. He's

the people's president.”

It is not hard

to spot the reasons for the public mood. In many ways, Brazil is doing

better than it has for a generation. Inflation is low and economic

growth is steadily rising. Aloizio Mercadante, who chairs the Senate's

economic-affairs committee, reels off many other positive numbers: the

current account is in surplus; the fall in the public debt is ahead of

target; the Central Bank's benchmark interest rate has fallen from

27.6% in 2002 to 12% today; total wages in the economy have grown by

8% over the past year; investment is up 7% over the same period; and

consumption has risen for 15 consecutive quarters.

| |

|

|

Brazil is

benefiting hugely from high world prices for its commodity exports and

abundant global liquidity, as well as from the economic reforms of

Lula's predecessor, Fernando Henrique Cardoso. “Lula is a lucky man,”

says Maílson da Nóbrega, a former finance minister. But he adds that

Lula has contributed to his own good fortune: he kept Mr Cardoso's

fiscal and monetary policies and gave the Central Bank operational

independence. By not hesitating to raise interest rates when inflation

threatened, the bank's governor, Henrique Meirelles, has won

investors' trust. That, together with the export boom, has brought a

steady appreciation of the real (see chart).

The strong

currency has helped to boost purchasing power, especially that of

poorer Brazilians for whom lower food prices are a particular boon (as

is a government anti-poverty programme that reaches 11m families). But

the currency's strength has some industrialists grumbling; the real is

overvalued by 20%, argues Paulo Skaf, the head of the São Paulo

federation of industry. Some Brazilian firms have responded by opening

factories abroad, from China to Argentina. The government this month

offered cheap credit to producers of shoes, textiles and furniture who

are struggling in the face of Chinese competition.

Mr Skaf and

others argue that the real's strength underlines the case for

structural reforms —of taxes, pension, labour laws and infrastructure

— in order to cut the cost of doing business. Brazil is still growing

more slowly than the world economy. Without reform, the sustainable

rate of growth is no more than 4% a year, many economists say. As Mr

Cardoso puts it: “we have to compete not with our past but with our

competitors.”

The government's

response is, in essence, that it does not believe in reform for

reform's sake. Franklin Martins, the president's press secretary,

argues that Brazil can grow at up to 5.5% a year without further

reforms. Any change to the labour laws that would take away rights

from those Brazilians who work in the formal economy is “not a

priority”, he says. Pension reform is, but only for new workers. He

adds that tax reform may be possible in two years' time, when the

government should need less money to pay its debts.

This may make

for mediocre economics but it is astute politics. Even the opposition

has lost much of its reformist impulse. Mr Cardoso's Party of

Brazilian Social Democracy (PSDB) has been disarmed by Lula's adoption

of many of its economic and social policies. Its former coalition

partner, the (conservative) Party of the Liberal Front, has changed

its name to the Democrats as part of a stampede for the middle ground

of Brazilian politics. The opposition's attempt to make corruption the

issue in last year's presidential election rebounded: most Brazilians

like and trust Lula, if not all of his followers. Besides, as life

improves, people are paying less attention to corruption and the legal

formalities of public life, laments Mr Cardoso.

In the medium

term, the chance of further reform may depend on the PSDB, which under

Mr Cardoso laid the foundations of economic stability and a stronger

democracy in the 1990s. The party has two plausible candidates for the

next presidential election in 2010 in José Serra and Aécio Neves,

respectively the governors of São Paulo and Minas Gerais. But it now

lacks a programme. “We have a good chance to be a governing party

again, but to do what?” asks Mr Cardoso. He says the PSDB needs to be

less scared of advocating modernisation, reform and further

privatisation.

Lula's Workers'

Party lacks a strong candidate to follow the president, who under the

constitution cannot run in 2010 (but might be able to in 2014). For

now, however, Lula stands supreme in Brazil. Rather than governing, he

reigns above party while “Brazil is on automatic pilot,” says

Gaudêncio Torquato, a political consultant in São Paulo. Unlike some

of its would-be air travellers, at least it has taken off.

Fonte: The Economist, 28/6/2007.

|